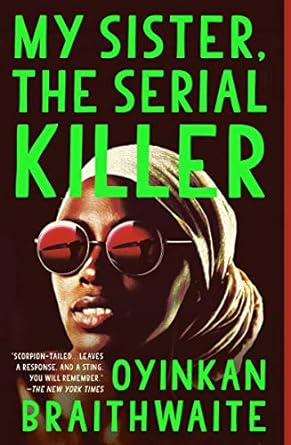

Category: Thrillers & Suspense

Regular price: $11.99

Deal price: $1.99

Deal starts: February 16, 2024

Deal ends: February 16, 2024

ONE OF TIME MAGAZINE'S 100 BEST MYSTERY AND THRILLER BOOKS OF ALL TIME • BOOKER PRIZE NOMINEE •“A taut and darkly funny contemporary noir that moves at lightning speed, it’s the wittiest and most fun murder party you’ve ever been invited to.” —MARIE CLAIRE Korede’s sister Ayoola is many things: the favorite child, the beautiful one, possibly sociopathic. And now Ayoola’s third boyfriend in a row is dead, stabbed through the heart with Ayoola’s knife. Korede’s practicality is the sisters’ saving grace. She knows the best solutions for cleaning blood (bleach, bleach, and more bleach), the best way to move a body (wrap it in sheets like a mummy), and she keeps Ayoola from posting pictures to Instagram when she should be mourning her “missing” boyfriend. Not that she gets any credit. Korede has long been in love with a kind, handsome doctor at the hospital where she works. She dreams of the day when he will realize that she’s exactly what he needs. But when he asks Korede for Ayoola’s phone number, she must reckon with what her sister has become and how far she’s willing to go to protect her.

Review BOOKER PRIZE NOMINEE • WINNER OF THE LA TIMES BOOK PRIZE FOR MYSTERY/THRILLER • FINALIST FOR THE WOMEN'S PRIZE"A taut, rapidly paced thriller that pleasurably subverts serial killer and sisterhood tropes for a guaranteed fun afternoon." —HUFFINGTON POST“It’s Lagos noir—pulpy, peppery and sinister, served up in a comic deadpan…This book is, above all, built to move, to hurtle forward—and it does so, dizzyingly. There’s a seditious pleasure in its momentum. At a time when there are such wholesome and dull claims on fiction—on its duty to ennoble or train us in empathy—there’s a relief in encountering a novel faithful to art’s first imperative: to catch and keep our attention… This scorpion-tailed little thriller leaves a response, and a sting, you will remember.” —NEW YORK TIMES“Campy and delightfully naughty…A taut and darkly funny contemporary noir that moves at lightning speed, it’s the wittiest and most fun murder party you’ve ever been invited to.” —SAM IRBY, MARIE CLAIRE “Braithwaite’s writing pulses with the fast, slick heartbeat of a YA thriller, cut through by a dry noir wit. That aridity is startling, a trait we might expect from someone older, more jaded—a Cusk, an Offill. But Braithwaite finds in young womanhood a reason to be bitter. At the center of these women’s lives is a knot of pain, and when it springs apart, it bloodies the world.” —NEW REPUBLIC“This riveting, brutally hilarious, ultra-dark novel is an explosive debut by Oyinkan Braithwaite, and heralds an exciting new literary voice… Delicious.” —NYLON"You can't help flying through the pages.." —BUZZFEED"Feverishly hot." —PAULA HAWKINS, author of GIRL ON THE TRAIN"Lethally elegant." —LUKE JENNINGS, author of KILLING EVE: Codename Villanelle"Disturbing, sly and delicious." —AYOBAMI ADEBAYO, author of STAY WITH ME“Oyinkan Braithwaite is rewriting the slasher novel, and man, does it look good. My Sister, The Serial Killer is a wholly original novel where satire and serial killers brush up against each other… A terrific and clever novel about sisterhood and blurred lines of morality.” —REFINERY29 “A rich, dark debut. . . . Evocative of the murderously eccentric Brewster sisters from the classic play and film “Arsenic and Old Lace,” . . . Braithwaite doesn’t mock the murders as comic fodder, and that’s just one of the unexpected pleasures of her quirky novel. . . . A clever, affecting examination of siblings bound by a secret with a body count.” —BOSTON GLOBE “A biting mix of wickedness and wit, Oyinkan Braithwaite weaves her narrative with a confidence that you've never read anything quite like it.” —INSTYLE"Braithwaite’s blazing debut is as sharp as a knife...bitingly funny and brilliantly executed, with not a single word out of place." —PUBLISHERS WEEKLY, (starred review)"Strange, funny and oddly touching...Pretty much perfect...It wears its weirdness excellently." —LITHUB"Who is more dangerous? A femme fatale murderess or the quiet, plain woman who cleans up her messes? I never knew what was going to happen, but found myself pulling for both sisters, as I relished the creepiness and humor of this modern noir." —HELEN ELLIS, author of AMERICAN HOUSEWIFE"A gem, in the most accurate sense: small, hard, sharp, and polished to perfection. Every pill-sized chapter is exemplary." —EDGAR CANTERO, author of MEDDLING KIDS"Sly, risky, and filled with surprises, Oyinkan Braithwaite holds nothing back in this wry and refreshingly inventive novel about violence, sister rivalries and simply staying alive." —IDRA NOVEY, author of THOSE WHO KNEW Amazon.com Review An Amazon Best Book of November 2018: Ayoola is the merriest murderer you ever did see. Young and beautiful, the favorite child, she’s on the phone to her older sister when My Sister, The Serial Killer opens, asking her to come quick. She’s just killed her boyfriend and needs help clearing the scene. It’s not the first time one of Ayoola’s boyfriends has met the business end of her blade, either. Older sister Korede, plain and overlooked, has drawn on her nursing training to clean up after two other hapless beaux. Who better to make blood disappear? And so far, Korede’s objections have been centered on classification ("Femi makes three, you know. Three and they label you a serial killer") rather than say, morality. As she says of her sister: “She needs me more than I need untainted hands.” But when the object of Korede’s desire, a doctor at the Lagos hospital where she works, becomes trapped in Ayoola’s web, fraternal loyalty collides with sibling rivalry, and one of these women is deadly with a knife. Darkly comic is a powerful understatement here; this short debut packs a brutal punch, crackling with glee and sly humor. Pages never turned so fast. —Vannessa Cronin --This text refers to an out of print or unavailable edition of this title. About the Author Oyinkan Braithwaite is a graduate of Kingston University in Creative Writing and Law. Following her degree, she worked as an assistant editor at Kachifo Limited, a Nigerian publishing house, and as a production manager at Ajapaworld, a children's educational and entertainment company. She now works as a freelance writer and editor. In 2014, she was shortlisted as a top-ten spoken-word artist in the Eko Poetry Slam, and in 2016 she was a finalist for the Commonwealth Short Story Prize. She lives in Lagos, Nigeria. --This text refers to the paperback edition. Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved. Words Ayoola summons me with these words—Korede, I killed him. I had hoped I would never hear those words again. Bleach I bet you didn’t know that bleach masks the smell of blood. Most people use bleach indiscriminately, assuming it is a catchall product, never taking the time to read the list of ingredients on the back, never taking the time to return to the recently wiped surface to take a closer look. Bleach will disinfect, but it’s not great for cleaning residue, so I use it only after I have first scrubbed the bathroom of all traces of life, and death. It is clear that the room we are in has been remodeled recently. It has that never-been-used look, especially now that I’ve spent close to three hours cleaning up. The hardest part was getting to the blood that had seeped in between the shower and the caulking. It’s an easy part to forget. There’s nothing placed on any of the surfaces; his shower gel, toothbrush and toothpaste are all stored in the cabinet above the sink. Then there’s the shower mat—a black smiley face on a yellow rectangle in an otherwise white room. Ayoola is perched on the toilet seat, her knees raised and her arms wrapped around them. The blood on her dress has dried and there is no risk that it will drip on the white, now glossy floors. Her dreadlocks are piled atop her head, so they don’t sweep the ground. She keeps looking up at me with her big brown eyes, afraid that I am angry, that I will soon get off my hands and knees to lecture her. I am not angry. If I am anything, I am tired. The sweat from my brow drips onto the floor and I use the blue sponge to wipe it away. I was about to eat when she called me. I had laid everything out on the tray in preparation—the fork was to the left of the plate, the knife to the right. I folded the napkin into the shape of a crown and placed it at the center of the plate. The movie was paused at the beginning credits and the oven timer had just rung, when my phone began to vibrate violently on my table. By the time I get home, the food will be cold. I stand up and rinse the gloves in the sink, but I don’t remove them. Ayoola is looking at my reflection in the mirror. “We need to move the body,” I tell her. “Are you angry at me?” Perhaps a normal person would be angry, but what I feel now is a pressing need to dispose of the body. When I got here, we carried him to the boot of my car, so that I was free to scrub and mop without having to countenance his cold stare. “Get your bag,” I reply. We return to the car and he is still in the boot, waiting for us. The third mainland bridge gets little to no traffic at this time of night, and since there are no lamplights, it’s almost pitch black, but if you look beyond the bridge you can see the lights of the city. We take him to where we took the last one—over the bridge and into the water. At least he won’t be lonely. Some of the blood has seeped into the lining of the boot. Ayoola offers to clean it, out of guilt, but I take my homemade mixture of one spoon of ammonia to two cups of water from her and pour it over the stain. I don’t know whether or not they have the tech for a thorough crime scene investigation in Lagos, but Ayoola could never clean up as efficiently as I can. The Notebook “Who was he?” “Femi.” I scribble the name down. We are in my bedroom. Ayoola is sitting cross-legged on my sofa, her head resting on the back of the cushion. While she took a bath, I set the dress she had been wearing on fire. Now she wears a rose-colored T?shirt and smells of baby powder. “And his surname?” She frowns, pressing her lips together, and then she shakes her head, as though trying to shake the name back into the forefront of her brain. It doesn’t come. She shrugs. I should have taken his wallet. I close the notebook. It is small, smaller than the palm of my hand. I watched a TEDx video once where the man said that carrying around a notebook and penning one happy moment each day had changed his life. That is why I bought the notebook. On the first page, I wrote, I saw a white owl through my bedroom window. The notebook has been mostly empty since. “It’s not my fault, you know.” But I don’t know. I don’t know what she is referring to. Does she mean the inability to recall his surname? Or his death? “Tell me what happened.” The Poem Femi wrote her a poem. (She can remember the poem, but she cannot remember his last name.) I dare you to find a flaw in her beauty; or to bring forth a woman who can stand beside her without wilting. And he gave it to her written on a piece of paper, folded twice, reminiscent of our secondary school days, when kids would pass love notes to one another in the back row of classrooms. She was moved by all this (but then Ayoola is always moved by the worship of her merits) and so she agreed to be his woman. On their one-month anniversary, she stabbed him in the bathroom of his apartment. She didn’t mean to, of course. He was angry, screaming at her, his onion-stained breath hot against her face. (But why was she carrying the knife?) The knife was for her protection. You never knew with men, they wanted what they wanted when they wanted it. She didn’t mean to kill him, she wanted to warn him off, but he wasn’t scared of her weapon. He was over six feet tall and she must have looked like a doll to him, with her small frame, long eyelashes and rosy, full lips. (Her description, not mine.) She killed him on the first strike, a jab straight to the heart. But then she stabbed him twice more to be sure. He sank to the floor. She could hear her own breathing and nothing else. Body Have you heard this one before? Two girls walk into a room. The room is in a flat. The flat is on the third floor. In the room is the dead body of an adult male. How do they get the body to the ground floor without being seen? First, they gather supplies. “How many bedsheets do we need?” “How many does he have?” Ayoola ran out of the bathroom and returned armed with the information that there were five sheets in his laundry cupboard. I bit my lip. We needed a lot, but I was afraid his family might notice if the only sheet he had was the one laid on his bed. For the average male, this wouldn’t be all that peculiar—but this man was meticulous. His bookshelf was arranged alphabetically by author. His bathroom was stocked with the full range of cleaning supplies; he even bought the same brand of disinfectant as I did. And his kitchen shone. Ayoola seemed out of place here—a blight in an otherwise pure existence. “Bring three.” Second, they clean up the blood. I soaked up the blood with a towel and wrung it out in the sink. I repeated the motions until the floor was dry. Ayoola hovered, leaning on one foot and then the other. I ignored her impatience. It takes a whole lot longer to dispose of a body than to dispose of a soul, especially if you don’t want to leave any evidence of foul play. But my eyes kept darting to the slumped corpse, propped up against the wall. I wouldn’t be able to do a thorough job until his body was elsewhere. Third, they turn him into a mummy. We laid the sheets out on the now dry floor and she rolled him onto them. I didn’t want to touch him. I could make out his sculpted body beneath his white tee. He looked like a man who could survive a couple of flesh wounds, but then so had Achilles and Caesar. It was a shame to think that death would whittle away at his broad shoulders and concave abs, until he was nothing more than bone. When I first walked in I had checked his pulse thrice, and then thrice more. He could have been sleeping, he looked so peaceful. His head was bent low, his back curved against the wall, his legs askew. Ayoola huffed and puffed as she pushed his body onto the sheets. She wiped the sweat off her brow and left a trace of blood there. She tucked one side of a sheet over him, hiding him from view. Then I helped her roll him and wrap him firmly within the sheets. We stood and looked at him. “What now?” she asked. Fourth, they move the body. We could have used the stairs, but I imagined us carrying what was clearly a crudely swaddled body and meeting someone on our way. I made up a couple of possible explanations— “We are playing a prank on my brother. He is a deep sleeper and we are moving his sleeping body elsewhere.” “No, no, it’s not a real man, what do you take us for? It’s a mannequin.” “No, ma, it is just a sack of potatoes.” I pictured the eyes of my make-believe witness widening in fear, as he or she ran to safety. No, the stairs were out of the question. “We need to take the lift.” Ayoola opened her mouth to ask a question and then she shook her head and closed it again. She had done her bit, the rest she left to me. We lifted him. I should have used my knees and not my back. I felt something crack and dropped my end of the body with a thud. My sister rolled her eyes. I took his feet again, and we carried him to the doorway. Ayoola darted to the lift, pressed the button, ran back to us and lifted Femi’s shoulders once more. I peeked out of the apartment and confirmed that the landing was still clear. I was tempted to pray, to beg that no door be opened as we journeyed from door to lift, but I am fairly certain that those are exactly the types of prayers He doesn’t answer. So I chose instead to rely on luck and speed. We silently shuffled across the stone floor. The lift dinged just in time and opened its mouth for us. We stayed to one side while I confirmed that the lift was empty, and then we heaved him in, bundling him into the corner, away from immediate view. “Please hold the lift!” cried a voice. From the corner of my eye, I saw Ayoola about to press the button, the one that stops the lift from closing its doors. I slapped her hand away and jabbed the ground button repeatedly. As the lift doors slid shut, I caught a glimpse of a young mother’s disappointed face. I felt a little guilty—she had a baby in one arm and bags in the other—but I did not feel guilty enough to risk incarceration. Besides, what good could she be up to moving around at that hour, with a child in tow? “What is wrong with you?” I hissed at Ayoola, even though I knew her movement had been instinctive, possibly the same impulsiveness that caused her to drive knife into flesh. “My bad,” was her only response. I swallowed the words that threatened to spill out of my mouth. This was not the time. On the ground floor, I left Ayoola to guard the body and hold the lift. If anyone was coming toward her, she was to shut the doors and go to the top floor. If someone attempted to call it from another floor, she was to hold the lift doors. I ran to get my car and drove it to the back door of the apartment building, where we fetched the body from the lift. My heart only stopped hammering in my chest when we shut the boot. Fifth, they bleach. --This text refers to an out of print or unavailable edition of this title.